Coregistration#

Coregistration between DEMs correspond to aligning the digital elevation models in three dimensions.

Transformations that can be described by a 3-dimensional affine function are included in coregistration methods. Those transformations include for instance:

vertical and horizontal translations,

rotations, reflections,

scalings.

Quick use#

Coregistrations are defined using either a single method or pipeline of Coreg methods, that are listed below.

Performing the coregistration on a pair of DEM is done either by using xdem.DEM.coregister_3d() from the DEM that will be aligned, or

by specifying the xdem.coreg.Coreg.fit() and xdem.coreg.Coreg.apply() steps, which allows array inputs and

to apply the same fitted transformation to several objects (e.g., horizontal shift of both a stereo DEM and its ortho-image).

Introduction#

Coregistration of a DEM is performed when it needs to be compared to a reference, but the DEM does not align with the reference perfectly. There are many reasons for why this might be, for example: poor georeferencing, unknown coordinate system transforms or vertical datums, and instrument- or processing-induced distortion.

A main principle of all coregistration approaches is the assumption that all or parts of the portrayed terrain are unchanged between the reference and the DEM to be aligned. This stable ground can be extracted by masking out features that are assumed to be unstable. Then, the DEM to be aligned is translated, rotated and/or bent to fit the stable surfaces of the reference DEM as well as possible. In mountainous environments, unstable areas could be: glaciers, landslides, vegetation, dead-ice terrain and human structures. Unless the entire terrain is assumed to be stable, a mask layer is required.

There are multiple approaches for coregistration, and each have their own strengths and weaknesses. Below is a summary of how each method works, and when it should (and should not) be used.

Example data

Examples are given using data close to Longyearbyen on Svalbard. These can be loaded as:

import geoutils as gu

import numpy as np

import xdem

# Open a reference DEM from 2009

ref_dem = xdem.DEM(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_ref_dem"))

# Open a to-be-aligned DEM from 1990

tba_dem = xdem.DEM(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_tba_dem")).reproject(ref_dem, silent=True)

# Open glacier polygons from 1990, corresponding to unstable ground

glacier_outlines = gu.Vector(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_glacier_outlines"))

# Create an inlier mask of terrain outside the glacier polygons

inlier_mask = glacier_outlines.create_mask(ref_dem)

The Coreg object#

Each coregistration approach in xDEM inherits their interface from the Coreg class1.

Each coregistration approach has the following methods:

fit()for estimating the transform.apply()for applying the transform to a DEM.apply_pts()for applying the transform to a set of 3D points.to_matrix()to convert the transform to a 4x4 transformation matrix, if possible.

First, fit() is called to estimate the transform, and then this transform can be used or exported using the subsequent methods.

Inheritance diagram of implemented coregistrations:

See Bias correction for more information on non-rigid transformations (“bias corrections”).

Nuth and Kääb (2011)#

Performs: translation and vertical shift.

Supports weights (soon)

Recommended for: Noisy data with low rotational differences.

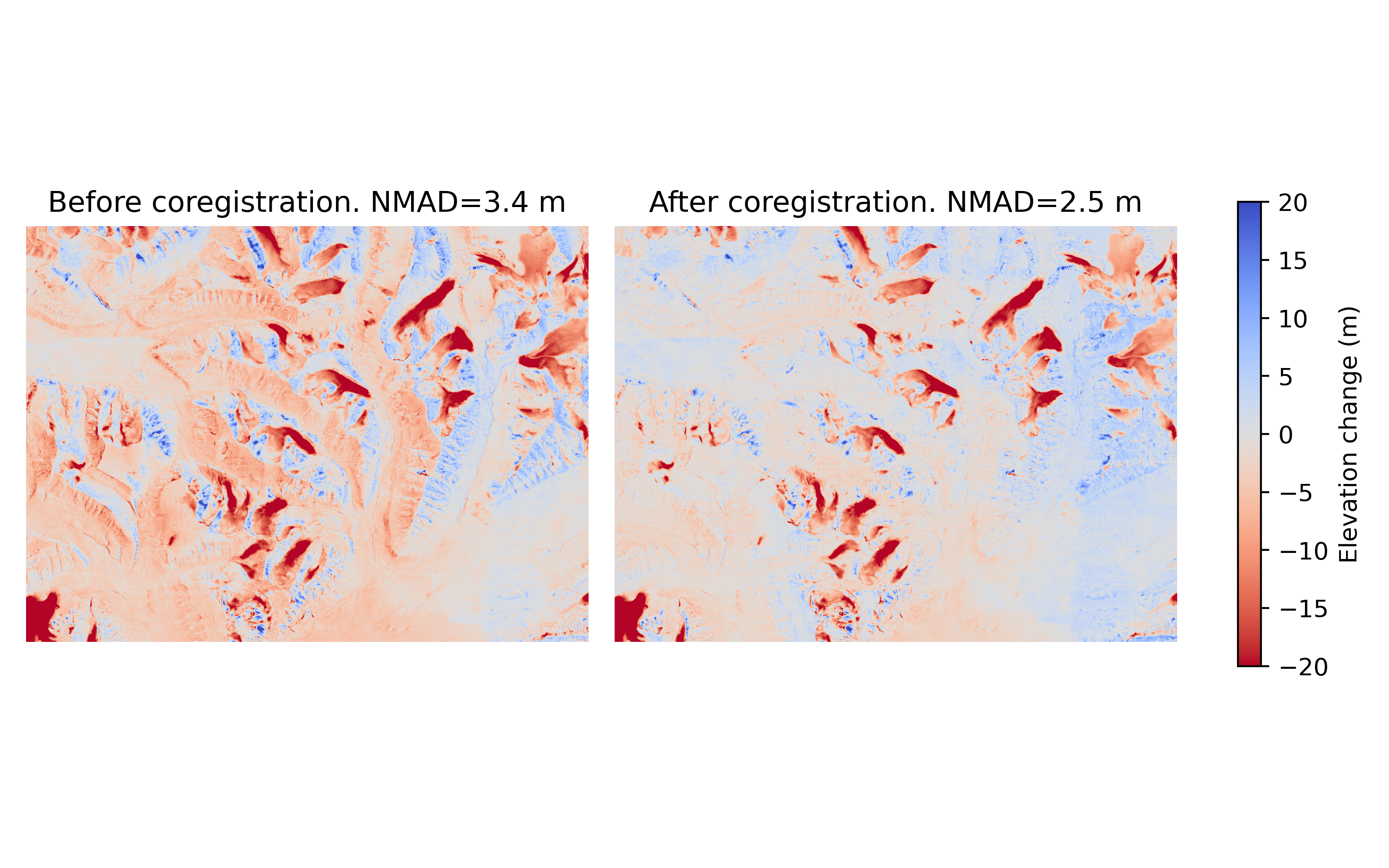

The Nuth and Kääb (2011) coregistration approach is named after the paper that first implemented it. It estimates translation iteratively by solving a cosine equation to model the direction at which the DEM is most likely offset. First, the DEMs are compared to get a dDEM, and slope/aspect maps are created from the reference DEM. Together, these three products contain the information about in which direction the offset is. A cosine function is solved using these products to find the most probable offset direction, and an appropriate horizontal shift is applied to fix it. This is an iterative process, and cosine functions with suggested shifts are applied in a loop, continuously refining the total offset. The loop stops either when the maximum iteration limit is reached, or when the NMAD between the two products stops improving significantly.

(Source code, .png)

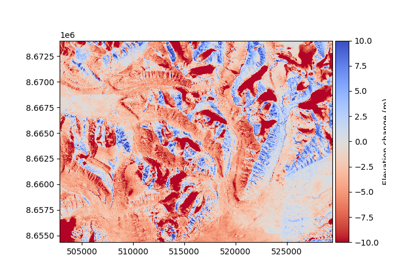

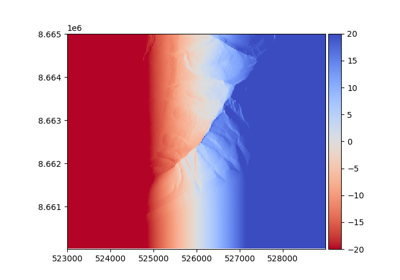

Caption: Demonstration of the Nuth and Kääb (2011) approach from Svalbard. Note that large improvements are seen, but nonlinear offsets still exist. The NMAD is calculated from the off-glacier surfaces.

Limitations#

The Nuth and Kääb (2011) coregistration approach does not take rotation into account. Rotational corrections are often needed on for example satellite derived DEMs, so a complementary tool is required for a perfect fit. 1st or higher degree [Deramping] can be used for small rotational corrections. For large rotations, the Nuth and Kääb (2011) approach will not work properly, and [ICP] is recommended instead.

Example#

from xdem import coreg

nuth_kaab = coreg.NuthKaab()

# Fit the data to a suitable x/y/z offset.

nuth_kaab.fit(ref_dem, tba_dem, inlier_mask=inlier_mask)

# Apply the transformation to the data (or any other data)

aligned_dem = nuth_kaab.apply(tba_dem)

Examples using xdem.coreg.NuthKaab#

Tilt#

Performs: A 2D plane tilt correction.

Supports weights (soon)

Recommended for: Data with no horizontal offset and low to moderate rotational differences.

Tilt correction works by estimating and correcting for an 1-order polynomial over the entire dDEM between a reference and the DEM to be aligned. This may be useful for correcting small rotations in the dataset, or nonlinear errors that for example often occur in structure-from-motion derived optical DEMs (e.g. Rosnell and Honkavaara 2012; Javernick et al. 2014; Girod et al. 2017).

Limitations#

Tilt correction does not account for horizontal (X/Y) shifts, and should most often be used in conjunction with other methods. It is not perfectly equivalent to a rotational correction: values are simply corrected in the vertical direction, and therefore includes a horizontal scaling factor, if it would be expressed as a transformation matrix. For large rotational corrections, [ICP] is recommended.

Example#

# Instantiate a tilt object.

tilt = coreg.Tilt()

# Fit the data to a suitable polynomial solution.

tilt.fit(ref_dem, tba_dem, inlier_mask=inlier_mask)

# Apply the transformation to the data (or any other data)

deramped_dem = tilt.apply(tba_dem)

Vertical shift#

Performs: (Weighted) Vertical shift using the mean, median or anything else

Supports weights (soon)

Recommended for: A precursor step to e.g. ICP.

VerticalShift has very similar functionality to the z-component of Nuth and Kääb (2011)_.

This function is more customizable, for example allowing changing of the vertical shift algorithm (from weighted average to e.g. median).

It should also be faster, since it is a single function call.

Limitations#

Only performs vertical corrections, so it should be combined with another approach.

Example#

vshift = coreg.VerticalShift()

# Note that the transform argument is not needed, since it is a simple vertical correction.

vshift.fit(ref_dem, tba_dem, inlier_mask=inlier_mask)

# Apply the vertical shift to a DEM

shifted_dem = vshift.apply(tba_dem)

# Use median shift instead

vshift_median = coreg.VerticalShift(vshift_func=np.median)

ICP#

Performs: Rigid transform correction (translation + rotation).

Does not support weights

Recommended for: Data with low noise and a high relative rotation.

Iterative Closest Point (ICP) coregistration, which is based on Besl and McKay (1992), works by iteratively moving the data until it fits the reference as well as possible. The DEMs are read as point clouds; collections of points with X/Y/Z coordinates, and a nearest neighbour analysis is made between the reference and the data to be aligned. After the distances are calculated, a rigid transform is estimated to minimise them. The transform is attempted, and then distances calculated again. If the distance is lowered, another rigid transform is estimated, and this is continued in a loop. The loop stops if it reaches the max iteration limit or if the distances do not improve significantly between iterations. The opencv implementation of ICP includes outlier removal, since extreme outliers will heavily interfere with the nearest neighbour distances. This may improve results on noisy data significantly, but care should still be taken, as the risk of landing in local minima increases.

Limitations#

ICP often works poorly on noisy data. The outlier removal functionality of the opencv implementation is a step in the right direction, but it still does not compete with other coregistration approaches when the relative rotation is small. In cases of high rotation, ICP is the only approach that can account for this properly, but results may need refinement, for example with the [Nuth and Kääb (2011)] approach.

Due to the repeated nearest neighbour calculations, ICP is often the slowest coregistration approach out of the alternatives.

Example#

# Instantiate the object with default parameters

icp = coreg.ICP()

# Fit the data to a suitable transformation.

icp.fit(ref_dem, tba_dem, inlier_mask=inlier_mask)

# Apply the transformation matrix to the data (or any other data)

aligned_dem = icp.apply(tba_dem)

Examples using xdem.coreg.ICP#

The CoregPipeline object#

Often, more than one coregistration approach is necessary to obtain the best results.

For example, ICP works poorly with large initial biases, so a CoregPipeline can be constructed to perform both sequentially:

pipeline = coreg.CoregPipeline([coreg.BiasCorr(), coreg.ICP()])

# pipeline.fit(... # etc.

# This works identically to the syntax above

pipeline2 = coreg.BiasCorr() + coreg.ICP()

The CoregPipeline object exposes the same interface as the Coreg object.

The results of a pipeline can be used in other programs by exporting the combined transformation matrix using xdem.coreg.CoregPipeline.to_matrix().

This class is heavily inspired by the Pipeline and make_pipeline() functionalities in scikit-learn.

Examples using xdem.coreg.CoregPipeline#

Suggested pipelines#

For sub-pixel accuracy, the [Nuth and Kääb (2011)] approach should almost always be used. The approach does not account for rotations in the dataset, however, so a combination is often necessary. For small rotations, a 1st degree deramp could be used:

coreg.NuthKaab() + coreg.Tilt()

Pipeline: [<xdem.coreg.affine.NuthKaab object at 0x7fbe437c8e50>, <xdem.coreg.affine.Tilt object at 0x7fbe437c8450>]

For larger rotations, ICP is the only reliable approach (but does not outperform in sub-pixel accuracy):

coreg.ICP() + coreg.NuthKaab()

Pipeline: [<xdem.coreg.affine.ICP object at 0x7fbe437bde90>, <xdem.coreg.affine.NuthKaab object at 0x7fbe437bdf10>]

For large shifts, rotations and high amounts of noise:

coreg.BiasCorr() + coreg.ICP() + coreg.NuthKaab()

Pipeline: [<xdem.coreg.biascorr.BiasCorr object at 0x7fbe437bcf90>, <xdem.coreg.affine.ICP object at 0x7fbe437bcf10>, <xdem.coreg.affine.NuthKaab object at 0x7fbe437bce90>]