Uncertainty analysis#

To analyze DEMs, xDEM integrates spatial uncertainty analysis tools from the recent DEM literature, in particular in Hugonnet et al. (2022) and Rolstad et al. (2009). The implementation of these methods relies partially on the package scikit-gstat for spatial statistics.

The uncertainty analysis tools can be used to assess the precision of DEMs (see the definition of precision in Analysis of accuracy and precision). In particular, they help to:

account for elevation heteroscedasticity (e.g., varying precision such as with terrain slope or stereo-correlation),

quantify the spatial correlation of errors in DEMs (e.g., native spatial resolution, instrument noise),

estimate robust errors for observations analyzed in space (e.g., average or sum of elevation, or of elevation changes),

propagate errors between spatial ensembles at different scales (e.g., sum of glacier volume changes).

Spatial statistics for DEM precision estimation#

Assumptions for statistical inference in spatial statistics#

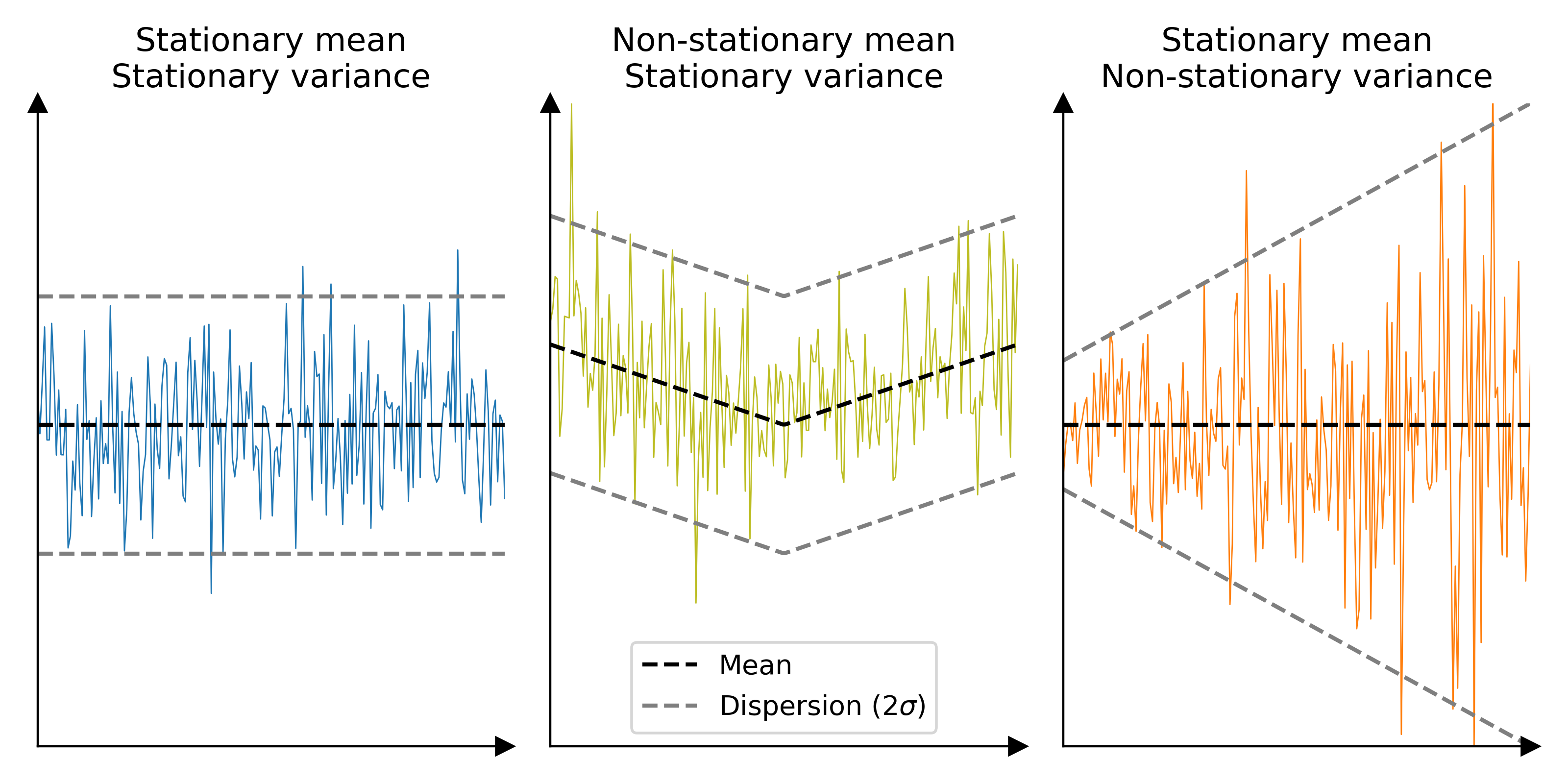

Spatial statistics, also referred to as geostatistics, are essential for the analysis of observations distributed in space. Spatial statistics are valid if the variable of interest verifies the assumption of second-order stationarity. That is, if the three following assumptions are verified:

The mean of the variable of interest is stationary in space, i.e. constant over sufficiently large areas,

The variance of the variable of interest is stationary in space, i.e. constant over sufficiently large areas.

The covariance between two observations only depends on the spatial distance between them, i.e. no other factor than this distance plays a role in the spatial correlation of measurement errors.

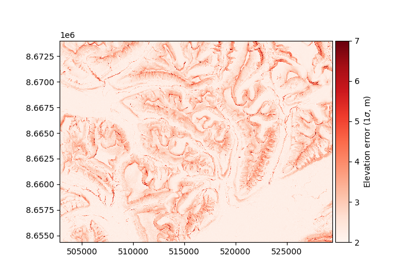

(Source code, .png)

In other words, for a reliable analysis, the DEM should:

Not contain systematic biases that do not average out over sufficiently large distances (e.g., shifts, tilts), but can contain pseudo-periodic biases (e.g., along-track undulations),

Not contain measurement errors that vary significantly across space.

Not contain factors that affect the spatial distribution of measurement errors, except for the distance between observations.

Quantifying the precision of a single DEM, or of a difference of DEMs#

To statistically infer the precision of a DEM, it is compared against independent elevation observations.

Significant measurement errors can originate from both sets of elevation observations, and the analysis of differences will represent the mixed precision of the two. As there is no reason for a dependency between the elevation data sets, the analysis of elevation differences yields:

If the other elevation data is known to be of higher-precision, one can assume that the analysis of differences will represent only the precision of the rougher DEM.

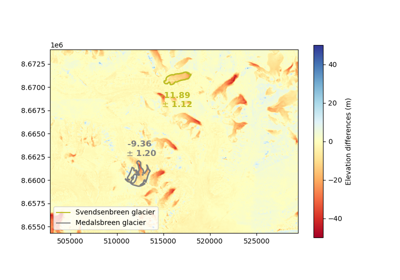

Using stable terrain as a proxy#

Stable terrain is the terrain that has supposedly not been subject to any elevation change. It often refers to bare-rock, and is generally computed by simply excluding glaciers, snow and forests.

Due to the sparsity of synchronous acquisitions, elevation data cannot be easily compared for simultaneous acquisition times. Thus, stable terrain is used a proxy to assess the precision of a DEM on all its terrain, including moving terrain that is generally of greater interest for analysis.

As shown in Hugonnet et al. (2022), accounting for Elevation heteroscedasticity is needed to reliably use stable terrain as a proxy for other types of terrain.

Metrics for DEM precision#

Historically, the precision of DEMs has been reported as a single value indicating the random error at the scale of a single pixel, for example \(\pm 2\) meters at the 1\(\sigma\) confidence level.

However, there is some limitations to this simple metric:

the variability of the pixel-wise precision is not reported. The pixel-wise precision can vary depending on terrain- or instrument-related factors, such as the terrain slope. In rare occurrences, part of this variability has been accounted in recent DEM products, such as TanDEM-X global DEM that partitions the precision between flat and steep slopes (Rizzoli et al. (2017)),

the area-wise precision of a DEM is generally not reported. Depending on the inherent resolution of the DEM, and patterns of noise that might plague the observations, the precision of a DEM over a surface area can vary significantly.

Pixel-wise elevation measurement error#

The pixel-wise measurement error corresponds directly to the dispersion \(\sigma_{dh}\) of the sample \(dh\).

To estimate the pixel-wise measurement error for elevation data, two issues arise:

The dispersion \(\sigma_{dh}\) cannot be estimated directly on changing terrain,

The dispersion \(\sigma_{dh}\) can show important non-stationarities.

The section Elevation heteroscedasticity describes how to quantify the measurement error as a function of several explanatory variables by using stable terrain as a proxy.

Spatially-integrated elevation measurement error#

The standard error of a statistic is the dispersion of the distribution of this statistic. For spatially distributed samples, the standard error of the mean corresponds to the error of a mean (or sum) of samples in space.

The standard error \(\sigma_{\overline{dh}}\) of the mean \(\overline{dh}\) of the elevation changes samples \(dh\) can be written as:

where \(\sigma_{dh}\) is the dispersion of the samples, and \(N\) is the number of independent observations.

To estimate the standard error of the mean for elevation data, two issue arises:

The dispersion of elevation differences \(\sigma_{dh}\) is not stationary, a necessary assumption for spatial statistics.

The number of pixels in the DEM \(N\) does not equal the number of independent observations in the DEMs, because of spatial correlations.

The sections Spatial correlation of elevation measurement errors and Spatially integrated measurement errors describe how to account for spatial correlations and use those to integrate and propagate measurement errors in space.

Workflow for DEM precision estimation#

Elevation heteroscedasticity#

Elevation data contains significant variability in measurement errors.

xDEM provides tools to quantify this variability using explanatory variables, model those numerically to estimate a function predicting elevation error, and standardize data for further analysis.

Quantify and model heteroscedasticity#

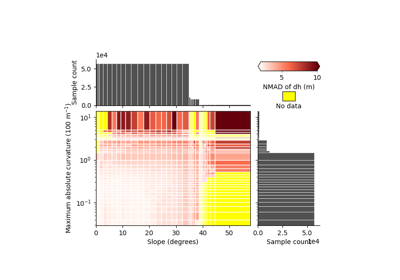

Elevation heteroscedasticity corresponds to a variability in precision of elevation observations, that are linked to terrain or instrument variables.

Owing to the large number of samples of elevation data, we can easily estimate this variability by binning the data and estimating the statistical dispersion (see

Measures of central tendency and dispersion) across several explanatory variables using xdem.spatialstats.nd_binning().

Show code cell source

import geoutils as gu

import numpy as np

import xdem

# Load data

dh = gu.Raster(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_ddem"))

ref_dem = xdem.DEM(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_ref_dem"))

glacier_mask = gu.Vector(xdem.examples.get_path("longyearbyen_glacier_outlines"))

mask = glacier_mask.create_mask(dh)

slope = xdem.terrain.get_terrain_attribute(ref_dem, attribute=["slope"])

# Keep only stable terrain data

dh.load()

dh.set_mask(mask)

dh_arr = gu.raster.get_array_and_mask(dh)[0]

slope_arr = gu.raster.get_array_and_mask(slope)[0]

# Subsample to run the snipped code faster

indices = gu.raster.subsample_array(dh_arr, subsample=10000, return_indices=True, random_state=42)

dh_arr = dh_arr[indices]

slope_arr = slope_arr[indices]

# Estimate the measurement error by bin of slope, using the NMAD as robust estimator

df_ns = xdem.spatialstats.nd_binning(

dh_arr, list_var=[slope_arr], list_var_names=["slope"], statistics=["count", xdem.spatialstats.nmad]

)

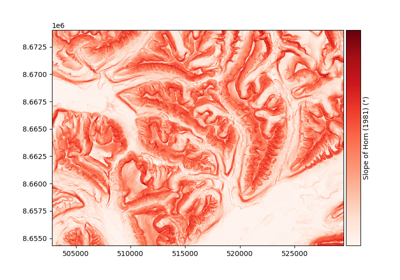

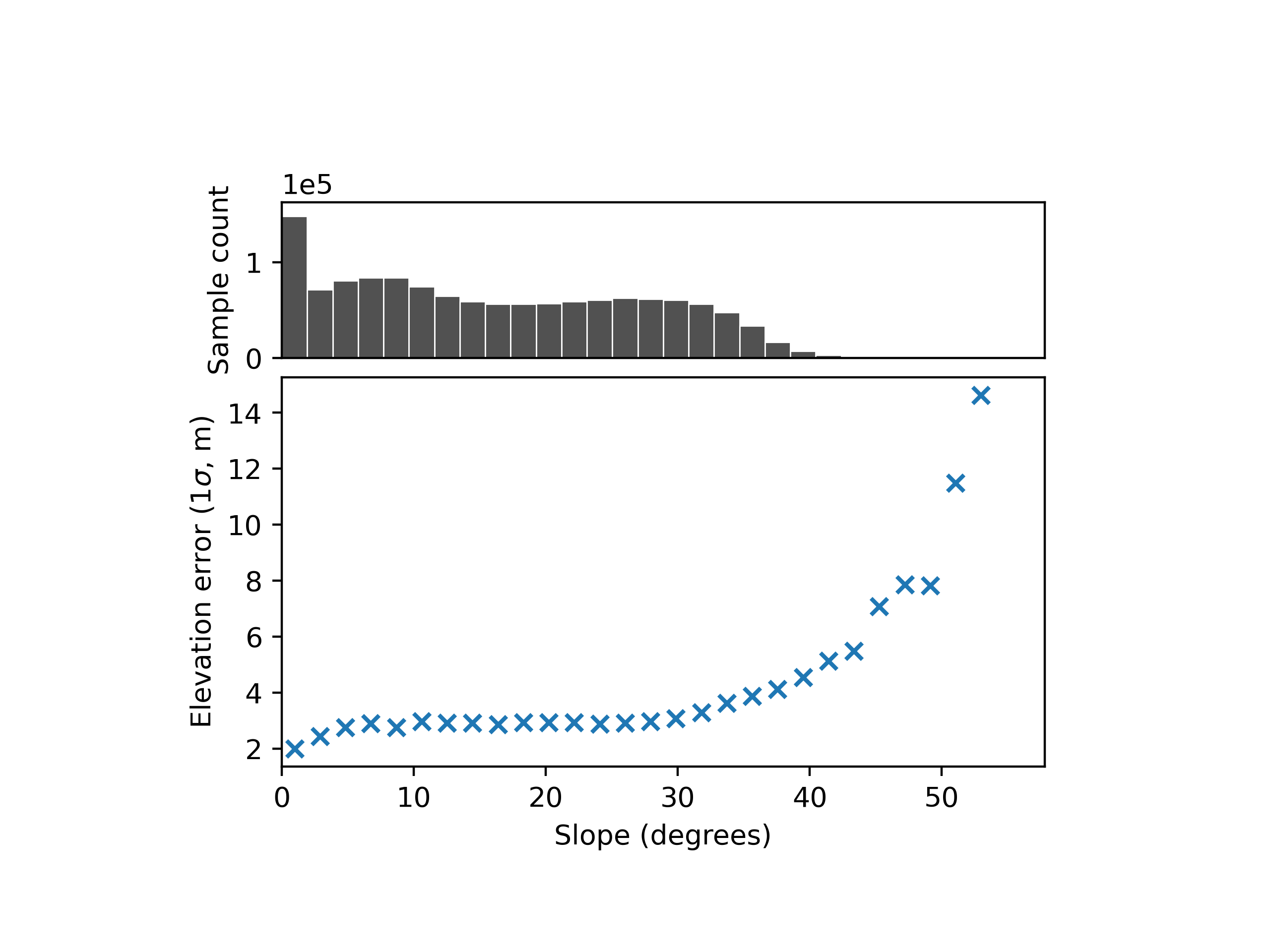

(Source code, .png)

The most common explanatory variables are:

the terrain slope and terrain curvature (see Terrain attributes) that can explain a large part of the terrain-related variability in measurement error,

the quality of stereo-correlation that can explain a large part of the measurement error of DEMs generated by stereophotogrammetry,

the interferometric coherence that can explain a large part of the measurement error of DEMs generated by InSAR.

Once quantified, elevation heteroscedasticity can be modelled numerically by linear interpolation across several

variables using xdem.spatialstats.interp_nd_binning().

# Derive a numerical function of the measurement error

err_dh = xdem.spatialstats.interp_nd_binning(df_ns, list_var_names=["slope"])

Standardize elevation differences for further analysis#

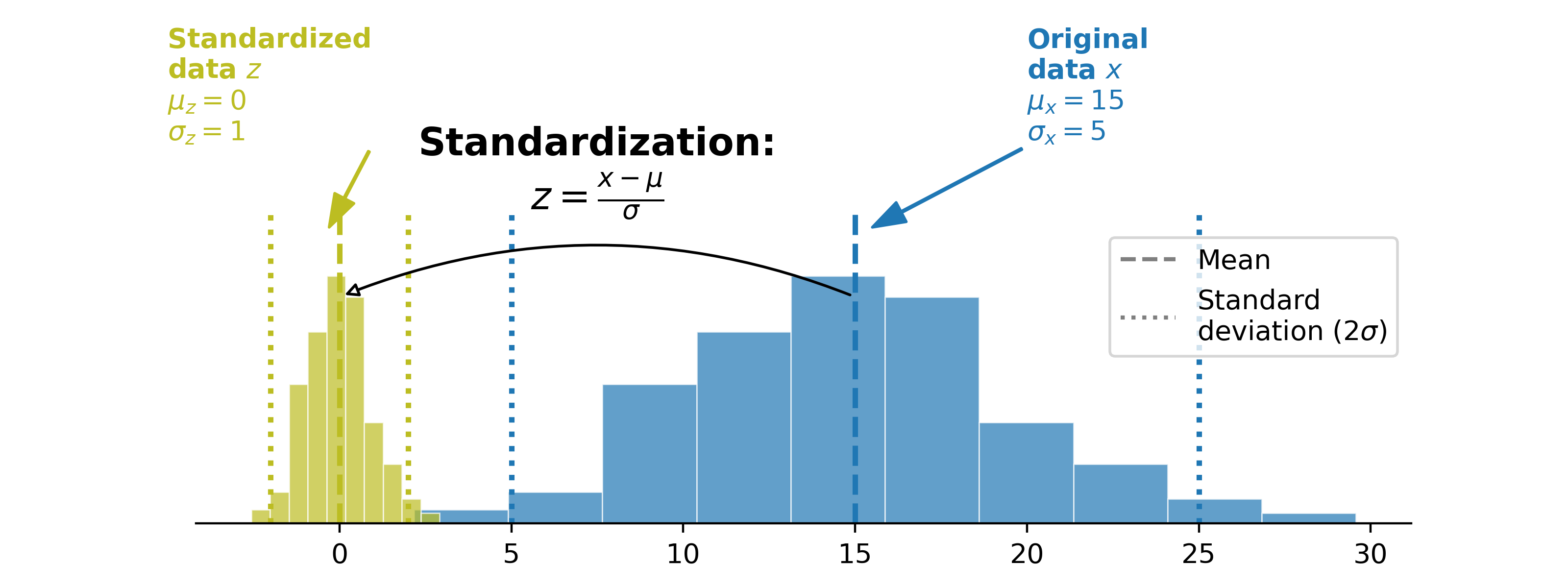

In order to verify the assumptions of spatial statistics and be able to use stable terrain as a reliable proxy in further analysis (see Spatial statistics for DEM precision estimation), standardization of the elevation differences are required to reach a stationary variance.

(Source code, .png)

For application to DEM precision estimation, the mean is already centered on zero and the variance is non-stationary, which yields:

where \(z_{dh}\) is the standardized elevation difference sample.

Code-wise, standardization is as simple as a division of the elevation differences dh using the estimated measurement

error:

# Standardize the data

z_dh = dh_arr / err_dh(slope_arr)

To later de-standardize estimations of the dispersion of a given subsample of elevation differences, possibly after further analysis of Spatial correlation of elevation measurement errors and Spatially integrated measurement errors, one simply needs to apply the opposite operation.

For a single pixel \(\textrm{P}\), the dispersion is directly the elevation measurement error evaluated for the explanatory variable of this pixel as, per construction, \(\sigma_{z_{dh}} = 1\):

For a mean of pixels \(\overline{dh}\vert_{\mathbb{S}}\) in the subsample \(\mathbb{S}\), the standard error of the mean of the standardized data \(\overline{\sigma_{z_{dh}}}\vert_{\mathbb{S}}\) can be de-standardized by multiplying by the average measurement error of the pixels in the subsample, evaluated through the explanatory variables of each pixel:

Estimating the standard error of the mean of the standardized data \(\sigma_{\overline{z_{dh}}}\vert_{\mathbb{S}}\) requires an analysis of spatial correlation and a spatial integration of this correlation, described in the next sections.

Examples that deal with elevation heteroscedasticity#

Spatial correlation of elevation measurement errors#

Spatial correlation of elevation measurement errors correspond to a dependency between measurement errors of spatially close pixels in elevation data. Those can be related to the resolution of the data (short-range correlation), or to instrument noise and deformations (mid- to long-range correlations).

xDEM provides tools to quantify these spatial correlation with pairwise sampling optimized for grid data and to model correlations simultaneously at multiple ranges.

Quantify spatial correlations#

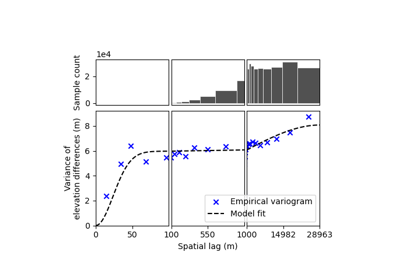

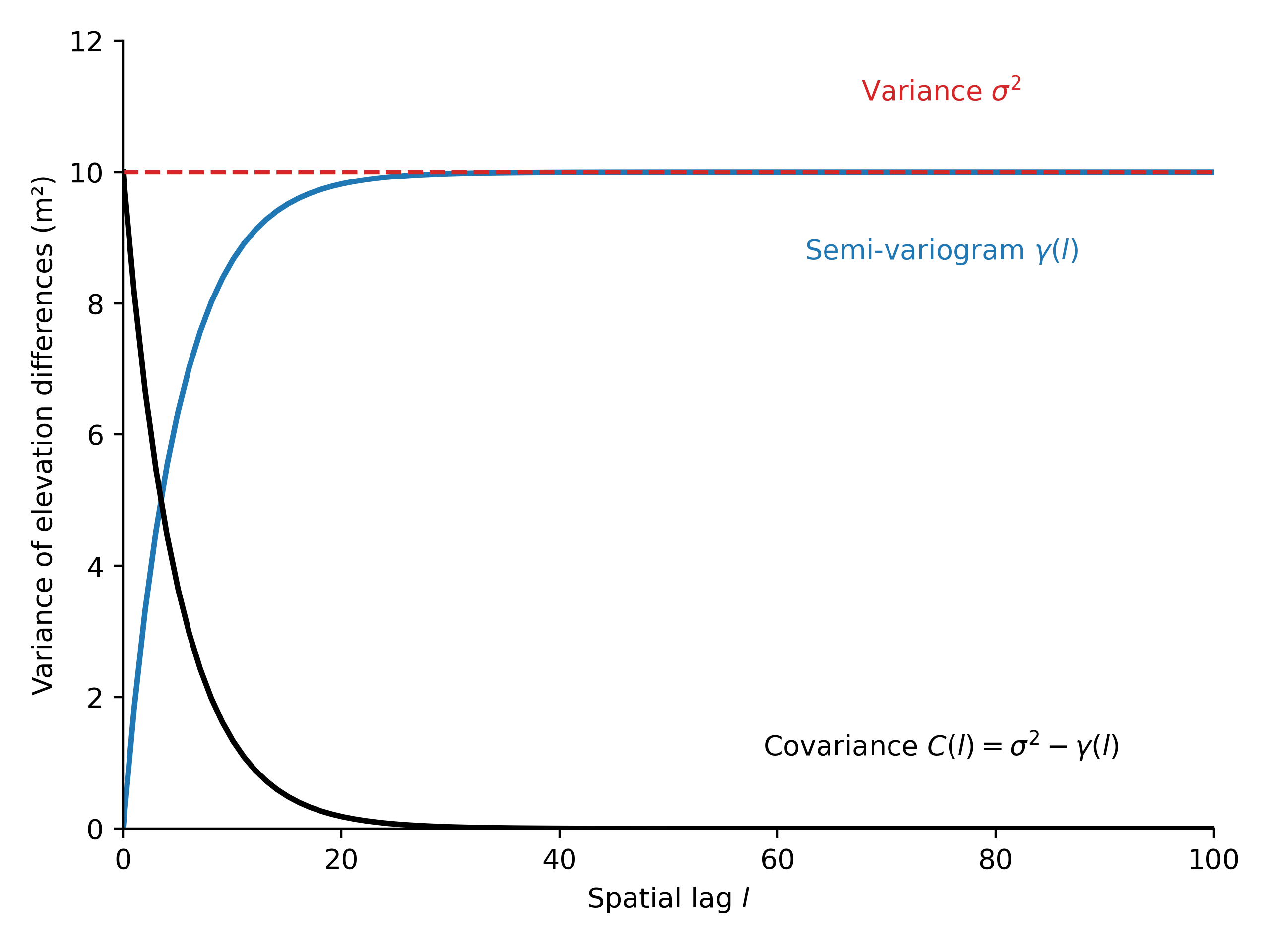

Variograms are functions that describe the spatial correlation of a sample. The variogram \(2\gamma(h)\) is a function of the distance between two points, referred to as spatial lag \(l\) (usually noted \(h\), here avoided to avoid confusion with the elevation and elevation differences). The output of a variogram is the correlated variance of the sample.

where \(Z(\textrm{s}_{i})\) is the value taken by the sample at location \(\textrm{s}_{i}\), and sample positions \(\textrm{s}_{1}\) and \(\textrm{s}_{2}\) are separated by a distance \(l\).

For elevation differences \(dh\), this translates into:

The variogram essentially describes the spatial covariance \(C\) in relation to the variance of the entire sample \(\sigma_{dh}^{2}\):

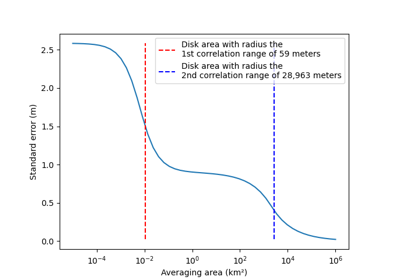

(Source code, .png)

Empirical variograms are variograms estimated directly by binned analysis of variance of the data. Historically, empirical variograms were estimated for point data by calculating all possible pairwise differences in the samples. This amounts to \(N^2\) pairwise calculations for \(N\) samples, which is not well-suited to grid data that contains many millions of points and would be impossible to comupute. Thus, in order to estimate a variogram for large grid data, subsampling is necessary.

Random subsampling of the grid samples used is a solution, but often unsatisfactory as it creates a clustering of pairwise samples that unevenly represents lag classes (most pairwise differences are found at mid distances, but too few at short distances and long distances).

To remedy this issue, xDEM provides xdem.spatialstats.sample_empirical_variogram(), an empirical variogram estimation tool

that encapsulates a pairwise subsampling method described in skgstat.MetricSpace.RasterEquidistantMetricSpace.

This method compares pairwise distances between a center subset and equidistant subsets iteratively across a grid, based on

sparse matrices routines computing pairwise distances of two separate

subsets, as in scipy.cdist

(instead of using pairwise distances within the same subset, as implemented in most spatial statistics packages).

The resulting pairwise differences are evenly distributed across the grid and across lag classes (in 2 dimensions, this

means that lag classes separated by a factor of \(\sqrt{2}\) have an equal number of pairwise differences computed).

# Sample empirical variogram

df_vgm = xdem.spatialstats.sample_empirical_variogram(values=dh, subsample=10, random_state=42)

The variogram is returned as a DataFrame object.

With all spatial lags sampled evenly, estimating a variogram requires significantly less samples, increasing the robustness of the spatial correlation estimation and decreasing computing time!

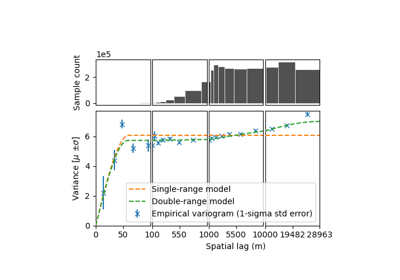

Model spatial correlations#

Once an empirical variogram is estimated, fitting a function model allows to simplify later analysis by directly providing a function form (e.g., for kriging equations, or uncertainty analysis - see Spatially integrated measurement errors), which would otherwise have to be numerically modelled.

Generally, in spatial statistics, a single model is used to describe the correlation in the data. In elevation data, however, spatial correlations are observed at different scales, which requires fitting a sum of models at multiple ranges (introduced in Rolstad et al. (2009) for glaciology applications).

This can be performed through the function xdem.spatialstats.fit_sum_model_variogram(), which expects as input a

pd.Dataframe variogram.

# Fit sum of double-range spherical model

func_sum_vgm, params_variogram_model = xdem.spatialstats.fit_sum_model_variogram(

list_models=["Gaussian", "Spherical"], empirical_variogram=df_vgm

)

Examples that deal with spatial correlations#

Spatially integrated measurement errors#

After quantifying and modelling spatial correlations, those an effective sample size, and elevation measurement error:

# Calculate the area-averaged uncertainty with these models

neff = xdem.spatialstats.number_effective_samples(area=1000, params_variogram_model=params_variogram_model)

TODO: Add this section based on Rolstad et al. (2009), Hugonnet et al. (in prep)